Bob and weave and hit pillows

- dtmillerlexky

- Apr 12, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 29, 2023

The Appalachian coal fields attract national attention in cycles, usually in one of two ways. In the past West Virginia occasionally played an outsize role in politics such as the hard-fought 1960 presidential primary, when both John F. Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey visited the state to secure its few but critical electoral college votes. That era seems to have passed.

The state is also a perennial favorite in surveys of the least healthy, poorest-educated, and least diverse, and many of these attributes stem from the deep history of poverty in the region, driven by economic booms and busts and low severance taxes paid to the state by faraway owners of extractive mineral rights, and the decline of the miners' union.

In addition to its poverty, West Virginia has one of the least diverse populations in the country, and that includes emigrants from other states. This wasn't always the case. From the earliest days of mining in southern West Virginia, in the first two decades of the twentieth century, mine owners were desperate for labor and recruited miners from Eastern Europe and even Central and South America, and Black workers were integrated into the workforce and the union earlier than in many other industries, though they were often given the harder jobs. But coal mining communities were isolated and, unless they were somehow involved with the coal industry outsiders were (and I believe still are) suspect.

In the mid-1960s, President Johnson's War on Poverty was well under way, casting the spotlight once more on Appalachian kids. My elderly grandfather Eli had no pension and qualified for only a small Social Security check but had always worked hard and it was difficult for him not to be able to contribute more to the household. With so many mouths to feed our family sometimes had no choice but to take advantage of the free commodities the government handed out. Eli took me with him to pick up our government cheese and powdered milk and corn meal and so on, and such staples made a real difference in the lives of many poor families.

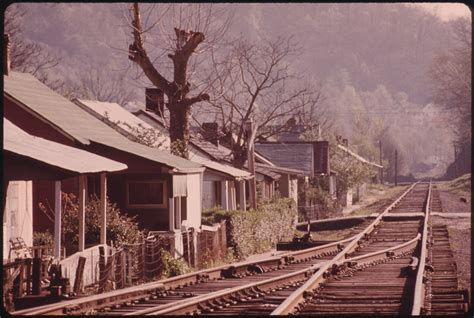

Some families in our little coal camp also saved money by creating their own small, illegal mines in the hillsides, digging enough coal in these "punch mines" for their household use. Occasionally a railroad car would derail, spilling coal along the trackside. Mothers and fathers and older children would hurry like ants to a picnic to shovel as much as they could into wheelbarrows before the company righted the railcar and scooped up the remaining coal.

As part of the War on Poverty, many idealistic VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America) workers came to the state, one of their goals being to organize locals to change the environmental laws governing mining corporations—laws written by and for the benefit of the companies. In that era, there was very little regulation to require them to address the damage their industry was causing, from flooded valleys to boulders falling into homes to the fouling of drinking water. The industry controlled the state capitol and staunchly resisted such reforms.

Power brokers at the local level also resented outsiders and saw VISTA volunteers as meddling hippies.

In addition to working for environmental reform some of these volunteers were assigned to mentor schoolkids. When I was in sixth grade at Mark Twain Junior High a young volunteer was supposed to help me with school work an hour or two a week but I didn't really need her help and we mostly just talked. She was a college graduate and had grown up in a mysterious place called New York City. I'd only heard the name and knew nothing about it and no one I knew had been there. I wanted her to tell me what it was like living in a city.

But our time was cut short: Fist fighting and bullying in general were common in the community, and fathers would often discipline kids (usually their own but sometimes others') with a belt. At one PTA meeting, a VISTA volunteer tried to broach the subject. She said there were other ways to correct misbehavior and other ways for kids to express their anger. Such as? asked the PTA chair. A different volunteer raised her hand and suggested that kids be taught to hit pillows instead of each other. The laughter among the locals started quietly but built quickly, and lasted until the volunteers walked out of the meeting, humbled. They weren't invited back and that was the end of VISTA at our school.

Soon the governor decreed that he would personally have to approve every single VISTA volunteer coming into the state and the group's numbers dwindled quickly. But in just a few years a raft of new federal legislation created the Environmental Protection Act and established new health and safety standards for miners, and VISTA workers were a small but important part of the coalition that successfully pushed for them.

I've often wondered what other kids who had VISTA mentors, even for a short period, took away from the experience. I was sorry to lose mine, but my brief time with her helped me imagine a world outside our hollers, a world of high-rise buildings, museums, city buses. A world where people talked back to power and fought to make their homes cleaner, safer, and more kind.

Comments