Book review for Kentucky Bench and Bar magazine

- David Thurman Miller

- Jan 8, 2023

- 13 min read

Updated: Mar 31, 2023

The Lives of Kentucky's United States Senators

(Bench and Bar Vol. 85, No. 5, September/October 2021, at 24)

Profiles of Kentucky's United States Senators 1792-Present by Paul L. Whalen summarizes the lives and times of each of the sixty-six men -- to date, all have been men -- who have represented Kentucky in the upper chamber of Congress. Whalen covers each in a few pages, in the chronological order of their service from the admission of Kentucky to the Union as the fifteenth state in 1792 through the present. He draws on newspapers, government archives, and the Congressional Record to place each senator within their historical context, and on their private papers and journals to provide a sense of their personal lives and political motivations.[1]

This chronological approach illustrates "how the U.S. Senate has grown in importance and power. During the first two decades of the nineteenth century, many senators resigned to go back to Kentucky and take 'lesser' positions as state court judges or in law practices. After the 1840s, that did not happen."[2]

The book breaks down Kentucky and national history into fifteen eras of a decade or two each, as viewed through these sixty-six lives. It tracks the rise and fall of the Democratic-Republican party, the Federalists, the Whigs, the short-lived Know Nothings or Nativists, the sharp intra-party divisions over slavery and states' rights leading to the Civil War and during Reconstruction, and the redefinition of the major political parties during the twentieth century.

Many historical issues are far too complex for a full explanation in capsule biographies and are referenced in Profiles only tangentially, and because the book covers every senator, the careers here range from the remarkable and consequential to the short-lived and obscure. The biographies succinctly cover their family backgrounds, professions, political affiliations and time in office through their deaths, situating their legislative work in the political currents of their times.

Early days of Kentucky

Many senators from the earliest days of Kentucky statehood are less well-known than later senators because the former were not full-time or career politicians and often had farms or businesses to run. Whalen notes that "between 1801 and 1819, only Senator John Pope served a full six-year term.[3] The pay for senators was relatively low and many had businesses or farms to run. “Between 1792 and 1820, Kentucky had over 18 different people serve as U.S. Senators in part due to resignations. [But] between 1992-2020, Kentucky has only had 4 different U.S. Senators.”[4]

The national political divide in the earliest days of Kentucky was generally between those favoring a strong, centralized government and banking system as championed by Alexander Hamilton versus a Jeffersonian Democratic-Republican party that was suspicious of centralized governmental authority. Kentucky politics was mostly anti-Federalist at the time, but the Kentucky legislature did elect Federalist Humphrey Marshall to the Senate in 1795, where he served until 1801. A skilled orator, Marshall talked his way out of being thrown into the Kentucky River by a mob angry over his support for a treaty with Great Britain that was opposed by Jefferson supporters.[5] Marshall may be better known for an incident from Marshall's post-Senate service in the Kentucky House, where he almost changed the course of American history; his duel with the young lawyer Henry Clay ended after three shots, leaving both men lightly wounded.

The Henry Clay era

Reading these capsule lives in succession gives a sense, especially for the first decades of the United States, of the many roles an aspiring political leader of that era might play in a short period of time -- representing Kentucky's root state of Virginia, serving in the state legislature of the new state of Kentucky, in the U.S. House and Senate, and as a representative of the U.S. President. Henry Clay would fill all these roles. He was also a lawyer of great skill and renown.

The career of long-serving statesman and would-be president Clay spans four of Profiles' era divisions, with the fourth (1832-1852) entitled "Domination by Henry Clay." Clay served all or part of four different Senate terms, served as Speaker of the House of Representatives and Secretary of State, provided early and crucial support for Thomas Jefferson. As historian David Broder of The Washington Post wrote, "Between Washington’s time and Lincoln’s, it is probable that no American was more influential than Clay.”[6] Clay's personal and public life have been well-documented in numerous biographies and Profiles concisely summarizes Clay's career across four Senate terms as he led the effort to hold the Union together in the decades leading up to the Civil War.

Both Clay's immediate predecessor, John Adair, and Clay's successor, David Meriwether, a cousin of the explorer Meriwether Lewis, are profiled despite the brevity of their service. John Adair (1805-1806), for example, was elected to complete the term of John Breckinridge (1801-1805), who resigned to become the U.S. Attorney General. Adair then resigned before his term had expired upon losing his reelection bid. Adair's life "was much more significant out of Washington than in it…[Adair] spent only a short session in Washington from December 1805 through April 1806."[7] The Kentucky legislature denied him a full term, leading to his resignation and the appointment of Clay for the remainder of Adair's term[8] while Clay was defending Aaron Burr on conspiracy charges in Frankfort. Clay would briefly return to the Senate to fill a second vacancy in 1810-11, then was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives before gaining his first full Senate term in 1831.

The sequence of events leading up to Meriwether's service is interesting for the political gamesmanship behind it. Clay had tendered his resignation in 1851, to be effective in late 1852, which would have enabled the majority Whig state legislature to appoint his successor. Instead, on Clay's death the Democratic governor appointed Meriwether[9] to fill Clay's unexpired term. Meriwether served only six weeks, not running in the special election to finish Clay's term of office, which was won by Whig Archibald Dixon.

The Civil War and Reconstruction

Even a short term of service as a senator could be illustrative of the political situation of an era. For example, John C. Breckinridge of the Lexington area, the youngest-ever U.S. vice president (under James Buchanan), was nominated as a pro-slavery candidate for president by a southern faction of the Democratic Party in the election of 1860, losing to the Republican, Abraham Lincoln. When the Civil War broke out, Breckinridge joined the Confederate forces and was expelled from the Senate barely nine months into his term. Breckinridge is emblematic of the complicated political divisions that have helped shape Kentucky as a state with conflicted loyalties, then governed at the state level by a Democratic Party resistant to much of the federal post-war efforts in the South.[10]

After the Civil War, Kentucky's Senate representation was dominated by men such as James Guthrie (1865-1868), who had supported the Union in the Civil War but opposed Reconstruction. Kentucky's dominant politics during the Reconstruction era included a strong contingent of former Confederates, such as John Stuart Williams (senator 1879-1885). Williams, a veteran of the Mexican War and eventually a Brigadier General for the Confederacy, represented the view of many Kentuckians who were "initially an anti-secessionist but abhorred President Abraham Lincoln's policies against slavery."[11]

Thomas Clay McCreery of Daviess County served twice as senator, 1868-71 and 1873-79. McCreery was a gifted public speaker and spoke vociferously against Reconstruction-era civil rights laws. In an interview McCreery, using a then-common racial slur, promised a newly elected black senator from Louisiana "some sleepless nights before he gets his seat."[12] McCreery was not alone: "The fact that five Republicans voted along with the Democrats [to deny the senator his seat] was a clear signal Reconstruction was losing steam, as evidenced by the end of formal Reconstruction in 1877."[13] "Jim Crow" laws were ascendant in Kentucky in the latter part of the nineteenth century, mandating among many other measures segregated schools[14] and separate railroad coaches and waiting rooms for white and colored passengers.

The Twentieth Century

Profiles breaks the twentieth century into seven distinct periods roughly corresponding to major events of the century -- World War I, Prohibition, the Great Depression, World War II and the Cold War, Civil Rights, Korea and Vietnam, and the post-Watergate era.

Kentucky's first Republican senator, former governor William O. Bradley, was elected to the Senate in 1908. Prior to the Seventeenth Amendment[15] effective in 1913, senators were chosen by state legislatures, with governors naming interim senators to fill unexpired terms of those who died or resigned. Where the majority party was internally split, however, this could result in compromise candidates from the opposing party, Bradley (senator 1909-1911) being a prominent example. Bradley had previously served as the first Republican governor of Kentucky (1895-1899) and though the Democratic majority in the state Senate had stymied much of his legislative agenda he passed significant anti-lynching legislation. In the legislative election for the U.S. Senate seat in 1907, after a long balloting process, enough Democratic legislators threw their support to the anti-Prohibition and pro-gold standard Bradley over Democrat J.C.W. Beckham, then completing his governorship. Beckham's Senate bid was undercut by the influential Henry Watterson and his Courier-Journal newspaper based on Beckham's gubernatorial record and support for Prohibition.[16]

Beckham would get his turn in the Senate in 1915, his fourth try at the nomination, winning as the first Kentucky senator elected under the then-new popular vote system established by the Seventeenth Amendment effective in 1913. His reelection bid in 1920 failed, however, in part because of his support for the Eighteenth Amendment[17] establishing Prohibition, to the detriment of the bourbon industry, and his opposition to women's suffrage via the Nineteenth Amendment.[18] Beckham kept trying for a political comeback, including a run for governor and another for the U.S. Senate, failing each time.

The twentieth century saw many Kentucky senators rise to national prominence and enjoy long periods of service, especially in the New Deal era and afterward. Five-term senator and Vice-President Alben Barkley, for example, was a congressman for fourteen years before his election to the Senate and served as Senate Majority Leader during the presidential administrations of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman. Barkley, despite some disagreements with Roosevelt, helped steer through New Deal legislation such as widespread rural electrification. He served as Vice-President -- the first so-called "Veep" based on a nickname bestowed by his grandson -- under Truman, with whom he grew personally close. Barkley was popular: "If you took a poll of senators as to the best loved man in the United States Senate, the winner -- among both Democrats and Republicans -- would probably be Alben Barkley of Kentucky."[19]

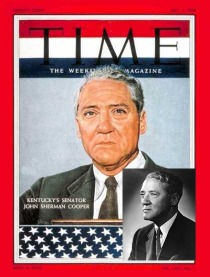

Barkley's emergence from post-vice presidency retirement to regain a Senate seat in 1954 has echoes of today: Then in his mid-seventies, some considered him too old to win re-election to the Senate but he defeated Republican incumbent John Sherman Cooper, giving Democrats control of that chamber by a single vote. By then Barkley was losing his eyesight and unable to read or speak with authority on legislation but remained highly respected. Though he had lost his Senate seniority by previously resigning, another senator offered to exchange seats with him, moving him from the freshman back row to the front row with senior senators. Barkley declined. He explained in a later speech, "I'm glad to sit on the back row, for now I would rather be a servant in the House of the Lord than sit in the seats of the mighty."[20] With that, Barkley collapsed and died of an apparent heart attack. He would be remembered for "his warm, human colorful qualities, for the respect and affection he evoked in others, not least of whom were the voters of Kentucky, who elected him time and time again…"[21]

The Senate has come a long way from the early days of "citizen legislators," with the average length of service of a senator continuing to trend upward, from a few years in the eighteenth and nineteenth century to the current average of well over twelve years, or two full terms.[22] In Kentucky, the average would be skewed by Senator McConnell of Louisville, now in his seventh term. The last single-term Kentucky senator was Marlow W. Cook (1968-74), also the state's last moderate-to-liberal Republican senator to date. He gave their first political experience to a young Mitch McConnell (as statewide youth director for his campaign) and John Yarmuth (as legislative assistant), now a U.S. Representative.

The era of joint service by Walter "Dee" Huddleston (senator 1973-85) and Wendell Ford (1974-99), friends as well as political allies, is illustrative of the influence exercised by senators with longer political careers. They served under four and five different presidents respectively across a politically turbulent post-Watergate era. Huddleston won his first term in 1972 upon John Sherman Cooper's retirement, becoming the first Democrat Kentucky had sent to the U.S. Senate in eighteen years, despite Richard Nixon's overwhelming presidential victory in Kentucky that year. Huddleston became known especially for his service on the committee charged with investigating intelligence agency abuses (popularly known as the Church Committee). In 1984 the moderate Democrat Huddleston faced a campaign dominated nationally and in Kentucky by the popularity of Republican President Ronald Reagan. Huddleston's opponent, Mitch McConnell, produced a series of memorable ads critical of Huddleston's Senate attendance record, featuring bloodhounds supposedly searching for Huddleston. McConnell won by a few thousand votes out of about 1.2 million cast and remains in office to this day.

Ford, a Democrat, was elected to the Senate in 1974 after three years as governor and remained in the Senate until 1999. He was especially known for defending Kentucky's chief economic engines -- coal, tobacco, whiskey, horses -- but he also helped shape national policy on telecommunications and aviation. When he was running for re-election in 1986, Ford produced his own commercial featuring a "hound dog" similar to the one McConnell had used against Huddleston. Ford said he "just wanted to make sure the hound dog was ours this year."[23]

Somerset native John Sherman Cooper was a circuit judge when he first ran for statewide office, losing the Republican gubernatorial primary in 1939. When Albert B. "Happy" Chandler resigned his Senate seat in 1945 to devote himself full-time to being Major League Baseball Commissioner Governor Simoen Willis appointed William Stanfill to fill the seat until the 1946 general election. Stanfill didn't run in that election, in which Cooper defeated the Democrat John Y. Brown Sr. Cooper quickly established a reputation in the Senate for independence with his support for a robust post-war rebuilding led by America and the Marshall Plan. One of the first bills he co-sponsored would drastically increase legal immigration to the U.S. of hundreds of thousands of Europeans displaced by war. A senator from Texas warned of admitting "subversives, revolutionists and crackpots." Cooper calmly replied that "These are people who resisted and will not return to a totalitarian state."[24] Democrat Virgil Chapman would defeat Cooper in the 1948 election for the full six-year term, aided by campaign appearances by President Truman and Vice President Barkley. Truman soon appointed Cooper a delegate to the United Nations.

Cooper was not done with the Senate, however. In 1952 he defeated Thomas Underwood for the remaining term of the seat to which Underwood had been appointed on Chapman's death. Cooper had star power on his side in the 1954 general election for a full term, including campaign appearances by President Eisenhower, Vice President Richard Nixon, and Senator Everett Dirksen. It wasn't enough, and Alben Barkley took the seat. President Eisenhower then named Cooper ambassador to India and Nepal. On Barkley's death the seat came open yet again and Cooper beat former Governor Lawrence Wetherby for the four years remaining in the term. Cooper finally won a full term in 1960 by a large vote margin and easily won re-election in 1966, again defeating John Y. Brown Sr.

By the end of his Senate service in 1972 Cooper had left his mark on everything from foreign relations and the Warren Commission to his support for civil rights legislation and opposition to American escalation of the war in Vietnam, often voting his own principles against Republican Party positions. Cooper rarely made speeches, describing himself as a "truly terrible public speaker,"[25] but when he spoke other senators listened. On one occasion Cooper sat nearby as Senator Joe McCarthy of Wisconsin railed against Winston Churchill, among many others, as being soft on communism. Cooper would have none of it. He recalled, "Well, that was so senseless, that I got up and said I'm surprised that the Senator from Wisconsin would make such an outrageous statement when you remember [Churchill's] tremendous courage, effort, in the war to save England and Europe against Hitler." The wall of fear McCarthy had built began to crack, leading to his eventual censure and decline. "[McCarthy] said, 'I'll remember you, you'll hear from me.' But I never heard from him. After the censure he went to pieces… Then no one ever paid any attention to him. I don't know, but probably, as they say in the hills of Kentucky, he just died out."[26]

[1] Acclaim Press, 2021. Mr. Whalen is an attorney in Fort Thomas, Kentucky, and a graduate of the Salmon P. Chase College of law He is a member of the Mediation Association of Kentucky and a former member of the Kentucky Board of Education and served as Administrative Law Judge in the Department of Workers' Claims. He is a former Campbell County Democrat Chairperson. The book surveys every senator regardless of their record. Another recent book, The U.S. Senate and the Commonwealth: Kentucky Lawmakers and the Evolution of Legislative Leadership (University of Kentucky Press 2019) by Senator Mitch McConnell and Roy E. Brownell II focuses specifically on the Kentucky senators who exercised formal or de facto leadership roles in that body or as vice presidents. [2] Text at 13. Between 1801 and 1819 only one senator, John Pope, completed a full term. [3] Text at 19. [4] Quoted in "Local Author Publishes History of Kentucky Senators," Feb. 23, 2021, http://www.fortthomasmatters.com/2021/02/local-author-publishes-history-of.html, retrieved July 23, 2021. [5] Text at 27. [6] July 5, 2010, review of Henry Clay: The Essential American, David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler (Random House 2010). [7] Text at 35. [8] Text at 36. Adair went on to become governor of Kentucky and served one term in U.S. House of Representatives, which Whalen describes as "unexceptional due to high absenteeism." [9] Until recently, when a U.S. Senate seat for Kentucky becomes vacant the governor named a person to serve until the next regular election for the seat. A total of sixteen senators attained office in this manner, some thus having remarkably short terms of service of months. [10]Whalen points out that Breckinridge's influence continued to be felt--his former law partner, the popular James Burnie Beck, served as senator from 1877 to 1890. [11] Text at 161. [12] Text at 143, quoting Nicholas Patler, Before Obama: A Reappraisal of Black Reconstruction Era Politicians, Volume I at 228. [13] Text at 143. [14]Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U.S. 45 (1908), upheld a state law forbidding black and white students attending the same school, or branches of the same school within twenty-five miles of each other. Berea college, established 1855, was the only integrated college in the South at the time. [15] Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Text at 163. [16] Beckham had been the lieutenant governor running mate to the assassinated William Goebel and assumed the office immediately on his death, Beckham's legitimacy eventually being settled by Taylor v. Beckham, 178 U.S. 548 (1900). He completed Goebel's term and then was elected for a full term in 1903. [17] Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, effective 1919. [18] Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, effective 1920. [19] Columnist Drew Pearson writing in the Long Beach Independent, Long Beach CA, July 19, 1948. [20] Text at 293, quoting Wilmington Morning News, Wilmington, Delaware, May 1 1956, 6. [21]New York Times, May 1, 1956, 32. [22] "Average Years of Service for Members of the Senate and House of Representatives, 1st - 111th Congresses," Congressional Research Services, 2010. [23] Text at 318, quoting Robert Barrett, "Sen Ford steals a page from McConnell--calls out the hounds in his latest TV ads," the Courier-Journal, Oct. 9, 1986. [24] Text at 266. [25] Quoted in "John Sherman Cooper Dies at 89; Longtime Senator From Kentucky." New York Times, Feb. 23, 1991, Section 1, 13. [26] Quoted in Oral History Interview: John Sherman Cooper, Marshall University January 1, 1979, 35. https://mds.marshall.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?artice=1029&context=oral_history, retrieved July 28, 2020.

Comments