Bound By a Book

- David Thurman Miller

- Jan 9, 2023

- 12 min read

Updated: Feb 27, 2023

A Father, a Son, and Half a Million Words. Originally published in Lexington Family Magazine. Thurman passed away on Veteran's Day, 2017.

"I've known your father more than half a century,” the letter began, “starting when our platoon was formed at Parris Island." The writer, "Scoop" Adams, was my father's commanding officer in K Company, Third Battalion, First Marine Division, in World War II--the Old Breed. Scoop described their experience in boot camp, their training in Cuba, and their landing on the island of Guadalcanal, where the U.S. began its first counteroffensive on Japanese-held soil. “The night before the landing we were told not to expect to survive,” he continued. The landing itself was unopposed, but within a few weeks many in their company were dead or severely wounded in some of the most ruthless fighting of the war, as the Japanese poured every available man and weapon into retaking the little island. Some marines were debilitated by strange tropical diseases, others swallowed up by jungle predators or monsoon. Others still functioned as soldiers, but were reduced to the bare outlines of human beings by the constant shelling and smell of death permeating the island. The company spent four months there, nearly starving as the Japanese cut off their supply lines, but in the end my father and his men took and held the island and secured America a crucial foothold in the South Pacific--and then the marines moved on to equally bitter fighting on other obscure islands.

I knew that much of the public story. New to me were the details Scoop and the other members of my father’s company shared with me by letter and in conversation. New-model rifles with wooden stocks that swelled to uselessness in the moist tropics. The taste of coffee grounds brewed eight times, with leaves and mud and motor oil mixed in. The sound of a dying friend, felled by a sniper, warning them not to try and rescue him.

I came to know these men through my father, Thurman, a gunny sergeant, one of the lucky. The public story of a war conceals many smaller wars, one man against one man, but more compellingly one man against himself, against his fear, and, if he lives, against what he has seen and done. My father survived Guadalcanal and other South Pacific battles to return stateside and teach at Camp Lejeuene--training young men barely in their twenties, future officers, to go back to the hell he’d just left and order other young men to certain death. When the war ended he came home to West Virginia and a new war began, as he took the only work he could find, deep in a coal mine. The malaria he’d held at bay took over and for years he was in constant pain and could eat little but skim milk, oatmeal and toast. His toenails and fingernails fell off as the result of an untreatable fungus infection. He startled awake many nights, haunted by the faces of the men he killed, or his friends who’d died just a few feet away from him, or those he ordered on suicide missions. Now we would call his condition post-traumatic stress syndrome, made much worse by the darkness and hard labor of the mines. On top of these came responsibility for a growing family. His dark moods and night terrors receded only gradually, with what must have taken tremendous willpower, to go from expecting, even wanting, to die to appreciating each day?

As a boy I knew the outlines of his life, that he had grown up in Depression-era Appalachia in a huge subsistence farming family, barefoot, without electricity, and without enough food for his large flock of brothers and sisters; that he had served in the war; and that he worked in the mines. Beyond that I knew little. Over the years I talked to him about his experiences from time to time, and although he patiently answered my questions the details never seemed to add up to a complete picture of the man. But I came to understand he had been able to put down in writing the things he could never say directly to anyone. He never had the opportunity for a college education--it was a struggle in the coal fields just to finish high school--but he nevertheless developed the habit of hammering out a few pages on his battered Royal manual typewriter about whatever was on his mind. Except for some letters to the editor he just filed everything away, including what I would discover later to be many pages of war memoirs, short stories, poems, songs, family lore, and historical fiction. I read some of it over the years and much of it was vivid, original. It gave me a much deeper insight into his experience. I suggested he publish it but he always refused, saying that he wrote for himself and never intended for the public to read it. I could see why, although I wondered whether it was because much of it revealed a thoughtfulness and tenderness that was hard to square with the life of a coal miner and ex-marine, or because much of it was harrowing, even disturbing, in describing what he’d seen and done.

But on his 80th birthday, after we chatted about our children, his grandchildren, his generation’s legacy, and the loss of so many veterans and friends, something changed; he agreed to publish it if I would help. I first simply edited it into a brief narrative of his life and made up bound copies for his friends and a few relatives, but I knew there was a larger audience for his story.

I've worked extensively as an editor and know how to build a book. To do it right can be time-consuming, and unless a major publisher gets behind it the author can spend a small fortune and have nothing to show for it except a closet full of unsold books, so I was hesitant to start down that path with him. Thankfully, a brief conversation with novelist and short story writer Gurney Norman prompted me to look into then-new online, cooperative publishers. These publishers do everything electronically, from the initial contracting through drafting, revision and final approval. Authors and editors do all the clerical and word processing work that accounts for the high cost of traditional publishing, so print-on-demand costs are low. Once the book is formatted it can be printed in small batches as needed, and authors hawk the book themselves, with a small royalty for books sold through other venues. My father and I agreed to become equal partners--he would write, and I’d do everything else. We settled on iUniverse as a publisher and I began sifting through what my father had written over the years, and began talking with his surviving friends and family. There was no shortage of material: In addition to hundreds of pages of his own writing he had ship manifests, service records, Japanese propaganda, my grandfather’s work journal, photos, audiotapes, scores of letters from his many brothers and sisters, and more, as well as a deep shelf of reference books. When people heard we were working on the book they came forward with many more photos and other material than we could possibly use.

With the same can-do spirit he brought to everything else my father mastered e-mail, and for months we exchanged messages almost daily, as I asked him to clarify a point or add detail, and he kept writing. After six months of steady work we had 250 solid pages for his first book, breaking naturally into three parts: a relatively happy if poor boyhood in the mountains, a long middle section covering the war years, and a final third describing three decades of life as a coal miner.

Only then did I begin to see my father’s life in full. Sifting through the material over and over made me realize that the values he adopted as a young man--singing to the mountains as he drove the family's few cattle home, sheltering barefoot in a hollow tree as a summer thunderstorm passed--nurtured him through the dark days that followed. Living off the land prepared him for the hellish South Pacific better than any urban upbringing could have, and probably saved his life. Attending the slaughter of farm animals gave him respect for the cycle of birth and death and rebirth, providing him hope for resurrection after the spiritual death of Guadalcanal and New Britain. And woven through it all was a deep sense of humor, incongruous in places but clearly key to his survival.

We published War and Work in 2003 and I built a simple website for him. He began to receive messages from all over the world, thanking him for his service and asking questions. For this and the books that would follow, I designed the covers, arranged other writers to contribute forewords, and handled the contracts, copyright filings, press releases, and so on, so he could concentrate on writing and responding to all the letters and e-mails. We arranged for signings at many area bookstores and even a few local television appearances. My father, then 82, pronounced himself very satisfied with the gift of having his story told so widely. And yet we had much more material still to work with.

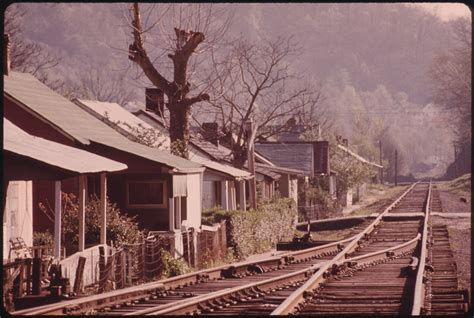

We followed up the first book with two more. Coal Bloom in 2003 focused on Appalachia and included a great deal of material we obtained from "old timers" and family friends about living in the country in the 1920's and 30's, in addition to my father's own still-sharp memories about the development of the coal industry. (A coal bloom is an outcropping of dark soil indicating a vein of rich coal beneath.) We commissioned original drawings of obscure farm implements to illustrate some of the stories he was telling. He wrote about being forced to move from the farm where he grew up when the company that owned the land began timbering and strip mining it, moving to the small coal camp of Helen, and about the absentee landlords who own West Virginia. He recalled miners being paid in private coal company money called “scrip,” his time as an official in the United Mine Workers of America union, and amplified his own memory of his war years with more interviews with surviving K Company members. The book led to more signings, television appearances, and even an invitation to speak at Mountain State University--a thrill for a man with only a high-school education. More e-mails and calls came from Australia, the Philippines, all over the world, and we even discovered both books had been translated into Japanese (without our knowledge or consent). Through all this he reconnected with many old friends, such as R.V. Burgin, author of Island of the Damned, and made hundreds of new ones.

Always Faithful, Always Free completed the trilogy in 2008, comprising material that didn’t quite fit the first two books plus more about his time in Cuba, where his outfit built the rudimentary outpost that would become the marine base camp at Guantanamo, and more about the year he spent recuperating in Australia between South Pacific deployments. My mother died not long before the book was complete and he wrote a long and tender section about their growing up together, courtship, the difficult war years, her care for him through his darkest hours, and 64 years of devoted and happy marriage. He described her long decline with a heartbreaking clarity, holding her hand as she passed and promising to be with her again soon.

The three books gradually got more and more attention. The National World War II Museum sent an interviewer from New Orleans to conduct a long session with him, followed by more book signings, a 70-minute documentary video interview, and much more. We learned that HBO was making a miniseries--The Pacific—about K Company and though he wasn't a named character in the miniseries he knew many of the real people the characters were portraying, leading to more interest in his story. Valor Studios interviewed him at length for their book series and flew both him and me to Eglin Air Force Base for a signing event and Emmy-watching party. (The Pacific won for best miniseries.)

Each of the three books sold only in the hundreds, but made him a small profit and accomplished what he wanted, to tell the story of his life and times. I began searching for a literary agent to represent my father in making a "real" book rather than a self-published one. In 2010 I edited all three books down to a single 45,000 word manuscript with a separate sample chapter covering a key battle, jettisoning anything that didn't propel his life story forward; I had faith in the inherent drama of his youth, wartime service, coal mining career, and long climb back to normalcy after his battle with malaria and post-traumatic stress disorder. I sent out hundreds of e-mails and samples looking for an agent, with only a few bites.

Finally, Scott Miller of Trident Media in Manhattan agreed to take the book on and sold it immediately to the prestigious St. Martin's Press, for a modest advance--modest in literary terms, but a windfall to us. My father and I used a chunk of our share to visit New York City, his first trip there. He was now 91 but showed little sign of it, delighting in the swirl and noise of the city. Trident had us take on a collaborator to get the book in final form, a young woman whose editing credits included a Pulitzer Prize-winning book, and she visited my father in West Virginia and interviewed him by phone several times. Her job would be to interact with publishing industry on our behalf, and help shape the final draft for the broadest readership. But as 2011 drew to a close and our January 1 deadline neared, personal issues kept her from doing much with the book, leaving its fate up in the air. We renegotiated our contract with her, obtained a deadline extension, and I took over her role. Meanwhile, my father continued to write daily, adding color and detail and helping track down names and dates and other marines and their families. His typing skills faltered as arthritis further gnarled the joints of his fingers, and his vision began to dim, but we adapted with a large-key keyboard and a bigger, brighter monitor. Several military historians stepped in to help and we located many previously unpublished or rarely seen documents and photos from the Marine Corps History Museum's archives and the Library of Congress. My brother Gilbert, an engineer, drew some rough maps to guide St. Martin's cartographers. Throughout, we were very aware that the literature of World War II is enormous, and we’d have to work hard to make this book stand out.

By May 2012, a solid 80,000-word first circulation draft of the book--now named Earned in Blood from a quote by Eisenhower--was ready. We sent copies to historians, novelists, and other authors to ask for book blurbs, and were astonished at the response. Homer Hickam, author of Rocket Boys and many other books, gave it a generous and appreciative reading, as did Denise Giardina, George Ella Lyon, R.V. Burgin, and many others, including a lieutenant colonel. (My father pronounced all this “not bad for gunny sergeant.”) Marc Resnick of St. Martin’s was a delight to work with, flexible and creative, and St. Martin’s earned its reputation for quality--through the rest of 2012 we carefully went over draft after draft, correcting smaller and smaller errors and adding more and more color and context.

The best moment came when we received a reply from Richard Frank, one of the most respected World War II historians and the author of the definitive book on Guadalcanal. Instead of a short blurb Frank wrote a long and glowing introduction for the book, praising it for showing not only the war but the Appalachian boyhood that preceded it and its cruel aftereffects--the delayed onset of malaria, the hallucinations, and the extraordinarily difficult prospect of managing those while working in the underground coal mines of the 1940's and 50's and raising a family. Frank put the book in perspective by framing it with R.V. Burgin's Island of the Damned and the landmark With The Old Breed by Eugene Sledge, the three books providing a unique collective portrait of a single combat unit from pre-boot camp through the final days of the war, with Earned in Blood providing a vivid and specific account of the arduous climb back to humanity so many soldiers faced. Even if not a single copy of Earned in Blood ever sold, Frank’s recognition meant a great deal to my father.

We reviewed the last galley proofs for Earned in Blood in December 2012 and the book was released in May 2013. It sold well and a paperback version was issued a few years later. The book became a Book of the Month Club selection and we had numerous book signings and appearances at veterans' events all over the eastern US. My father turned 93 that November and described himself as in the bonus years of his life. He showed little sign of declining mentally, even as the rigors of time and disease manifest in his slowing gait and shakier signature. I promised myself that our partnership would be done when I laid the first hardbound copy of Earned in Blood down in front of him. But he already had plans for a final book, just about coal mining. [That was eventually published as Miner: A Life Underground.-Ed.]

The mythologist Joseph Campbell said that all heroes, whether Ulysses or Luke Skywalker, share the same basic story. As he prepares to leave a sunny childhood he’s faced with a challenge that requires him to choose: He may choose a path that leads to victory or to dissolution and failure, but he must choose. He cannot stand at the crossroads. The hero inevitably descends into darkness, be it the belly of a whale or the moral chaos of war, and faces a demon, often one representing some troubling aspect of his own nature. Even if he defeats the demon he faces a long and difficult journey home, back to the light, changed forever by the ordeal. But he brings a hard-won wisdom to his people.

Every family has its own mythology connecting its members to larger, even historic forces. Neither my father nor I knew until we started researching the first book that his great-great-grandfather was the first postmaster and schoolteacher in what was then the most rural part of southwestern Virginia. I like to believe that this ancestral regard for education is expressed in my own father's habit of reading and writing, and that a natural love of learning will flower in my own children. I want them to understand that my father’s heroic journey, from the sunny pre-strip mining hills of West Virginia through the figurative darkness of the war and the literal darkness of the coal mines, and his long, slow walk back into the light was made possible by the belief that he was fighting for a future in which the most degraded man could rebuild himself as a steady, honest worker, a faithful husband, a patient father. I want them to believe that like their grandfather they are bred in the bone with the strength to meet their own challenges, large or small, with courage, generosity of spirit, and especially a sense of humor. His life demonstrates that not only is that one way to live, it's the only way.

Comments