Pigpen Bottom

- dtmillerlexky

- Jul 6, 2023

- 3 min read

Another short excerpt from my memoir A Standing Start.

There were (and are) no stop signs or traffic lights in our little coal camp of Helen and the whole town wasn't much longer than a football field, except for the half-mile road leading to the town's second mine.

A single cross-street, perpendicular to Route 16, led east up past the community church and what were once general laborers' houses to the predominantly Black housing section called Berry Branch, and then up the holler to one of the two mines. The road to the west, called Upper Bottom, was much shorter and ran past the company store and the nine foremen's houses, then up a hillside past the superintendent's house to the town's second mine. By design, virtually anywhere in town could be seen from the super's enormous house, which must have had ten bedrooms, though I was never inside. At the very southern end of Helen a short unpaved spur road bent west, leading to twelve houses in the Lower Bottom.

Foremen's houses had two stories and four bedrooms and were well-built, with beautiful native cherry stairs and plastered walls. Except for Route 16, which sliced the town length-wise, the hundred feet of road in the Upper Bottom was the only paved street in town.

The houses along Route 16 and up Berry Branch were all one-story and not nearly as well-built as the foremen's houses but were sturdy and were coveted by workers with some seniority with the company.

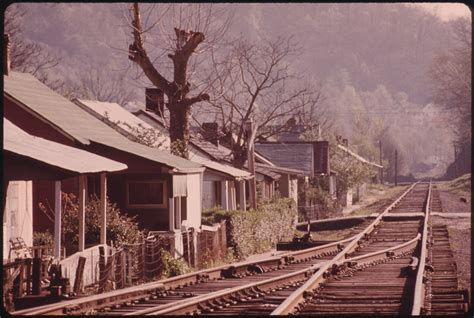

By contrast, the houses in the Lower Bottom, the only place my father could find affordable houses for our large extended family, were the simplest-built in town—so simply built they could have been mistaken for chicken coops. They were intended for the lowest strata of general laborers and itinerants.

Train cars full of coal ran incessantly on tracks only a few feet from the Lower Bottom houses, carrying thousands of tons of coal each day from still-working mines in the region. The C&O and Virginian Railroads ran along each side of the town in Helen, parallel to Route 16, and a small stream fed by both Berry Branch and the runoff from Tams Mountain followed the tracks, each little town adding its untreated wastewater. The joined streams became the Winding Gulf watershed and eventually fed the Guyandotte River in Mullens to the south.

The railroad tracks parenthesized the narrow little town and the grime from all that coal was often visible as a gray suspension in the air, settling thickly as soon as a surface was cleaned or painted. Because of the dirt road, the rough houses, the dirty stream, and the fact that several families kept pigs, the Lower Bottom where we came to live was universally referred to as Pigpen Bottom.

Helen, at the southernmost end of Raleigh County and just a few miles from the northern tip of Wyoming County, was originally laid out in 1919 and like almost all in that area and era was designed to be a company town, with everything provided by, and controlled by, the company. Mining and timber companies in the early to mid twentieth century had difficulty hiring and retaining reliable workers; since roads were poor or nonexistent, it was in the companies' best interests to provide amenities to attract and keep workers, both families and single men. Helen and many other "model" camps of that era had a movie theater, bowling alley, post office, baseball field, clubhouse, and barbershop. It even had its own telephone exchange. There was also a small sandwich grill and, above that, tiny apartments for bachelor miners. The coal dust on a miner after a shift in the mine was deep and thick, and because many houses had no tubs or showers, every coal camp including Helen had a large communal bathhouse. The tradeoff for all this was that until the 1950s miners were paid in a private currency, called "scrip," that was good only at the particular company's store. Miners had little choice but to pay the store's inflated prices.

The available coal in both of Helen's mines had been almost exhausted by the time I was born, so the miners had begun looking for work elsewhere, and the town's amenities closed down one by one. Eighty percent of the town's nearly one thousand residents moved away within a few years. Many houses were simply left to fall in, or were torn down for their lumber, if it could be reused. Arson was common in whatever was left, and almost every communal structure in Helen except the church was torn down, burned down, or abandoned by the time I was ten. There was no fire department anywhere near; if a building caught fire it would almost certainly burn completely. But as long as the abandoned buildings stood, we kids were free to roam their ghostly, echoing interiors.

Comments