The original Otsego Quartet

- dtmillerlexky

- Mar 23, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 24, 2023

Even at his lowest, in those lean, hard years after the war, my father loved to sing, always had. As a boy bringing in cows from the hillsides on the family farm, in church, around the house, it didn't matter. It helped that there were other good singers in the family, a sister and two cousins especially, who were also taken with music, though none had any training in it; it was just something in the air, born in that great silence of the 1920s, before voices began to magically whisper from little boxes.

There was little music during my father's time in the second world war, other than Taps; the soundtrack was shells and gunfire and clipped military orders. He brought home souvenirs—PTSD, an untreatable fungal infection, and liver disease, and it would take him years to regain his health.

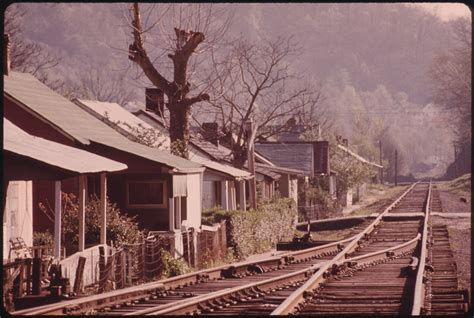

Now the war was over and he was back home, with a loving wife and a new baby. He worked in the coal mine, the only job he could find, always on the night shift to spare his family his recurrent nightmares. He knew he was in no shape to be a good father or husband. He started going to church, to the same relatively tolerant Baptist sect our immediate family had always belonged to. He found he could sing there and not think about anything, his tenor joining in with the congregation's.

Our large family was close and he soon met back up with a cousin on his mother's side and her husband, a soprano and bass respectively, both friends from childhood. The trio sang together and soon recruited my father's baby sister Kathleen on alto, to make it a quartet. They sang at each others' churches and were invited to sing at the many community events that welcomed free music. My father learned and then taught classes in the traditional "shaped note" singing that was more popular than standard musical notation in that region, in that era.

The cousin's daughter, who'd gone off to college and come back home to teach music, was recruited to play piano for them. Their repertoire expanded to cover much of what was popular then, from the beautiful simplicity of "In the Garden" to the most mawkish altar calls. Their sound was a little different, with my father and his sister flipping the tenor and alto parts in unexpected places; not being trained musicians, sometimes one would get lost and the other would take up their line to cover for them. They also imitated some other Southern groups who had begun syncopating their songs—there was nothing about it in the Bible one way or the other. The piano player dropped in major sevenths or other touches here and there, little grace-note amens.

In 1950 the five of them were offered a live half-hour weekly show on tiny radio station WWYO, which had been licensed the previous year. Most of the time the little studio's thousand watts reached no more than twenty miles, but when atmospheric conditions were right the hollows acted as an amplifier and carried the voices and music as far as Bluefield. Short sets of fifteen or thirty minutes were common filler then, before the age of prerecorded commercials; the gospel songs were palate-cleansers between hardcore old-time hillbilly acts like the duo Scotty and Tar Heel Ruby and their band The Dixie Border Boys, all the shows culminating in the evening-long "Wyoming Hayride" on Saturday night. Most of the station's content was live, since the process of cutting material to acetate was relatively expensive and time-consuming, so the musicians and announcers worked a lot. My father's family group was sometimes called to fill in for other acts, but only accepted evening work so he could sleep during the day.

As the Otsego Quartet performed together, my father began to look forward to those evenings at the station. He would be due for work at ten each night, just a few miles south of the studio, so would be singing during his "morning" before descending into the mine for his shift. I always wondered if those sessions were a kind of dawn prayer against roof falls and short fuses and high voltage.

One night at the studio late in 1951 someone—there are vague memories of a youngish man in a nice hat—heard the group sing and thought they should make some records. The Carter family had hit it big a decade earlier, selling thousands of records and broadcasting their twice-daily show on a megawatt border radio station out of Mexico, where the owner shilled fake medical cures using goat glands. My father and aunt's foursome had similar harmonies to the Carters, as many groups did at the time.

The next week the young man was back at WWYO, and the quartet and pianist gave it a shot, using the studio's Presto recording equipment to cut six songs direct to acetate discs, each in one take. He took the discs and said he'd let them know. A few weeks later the man sent the acetates back. They sounded terrible. The manager's explanation was that the engineer, his name now lost to history, was drunk; he was fine for running a live show but, apparently, not the close work of recording.

The quintet hadn't expected anything to come of it anyway and never tried again. Soon the arrival of more children (in my father's case, my sister and then me) and hard jobs and caring for their aging parents left all the cousins little time for making music. They gave up the radio show and saw each other only at occasional family get-togethers. In the meantime, radios got better and smaller and my father sang more than gospel around the house—Johnny Cash, snatches of pop tunes.

I'm sure he wouldn't have traded his time with his sister and cousins for the world. He got what he wanted out of those many hours, just learning to be a human being again.

The acetates sat atop each other in a closet for decades and were damaged in a flood before being digitized. Not much could be done to improve their sound, considering their age, scratches, and their original engineering.

Comments