Tit for Tat and Law and Order

- dtmillerlexky

- Jun 21, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Apr 11, 2024

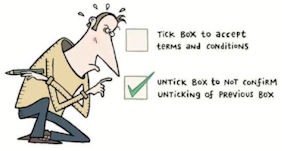

Two guys agree to rob a bank and promise that if they're caught they'll not rat out the other. The rob the bank but are nabbed before they can get away. They're taken to separate interview rooms at the police station and can't communicate with each other. The evidence against them is iffy, so they're each offered a plea deal: Confess and implicate the other and you'll go free. If both stay silent they each get one year in prison. If both confess they get two years each.

This is a classic "Prisoner's Dilemma," and it plays out not just in every police procedural on television but in real life as well. What's the best strategy for the robbers? Obviously, it would be best for one to confess and implicate the other in hopes of walking free. But the other guy is thinking the same thing and is taking a chance the other one will rat him out.

The question is, in game theory terms, when should one robber "cooperate" with the other (say nothing, so both get a shorter term) and when should one "defect" (confess, saving their own hide by implicating the other guy)? There's no one "right" answer, just as there's no right answer in analogous game-theory situations in business or international diplomacy or nuclear weapons strategy. The game theory behind the Prisoner's Dilemma has revolutionized fields as disparate as the psychology of addiction and international climate negotiations.

The entirety of human evolution is just an endless series of game theory questions—who should I share my food with? Should I take this other person's land? Are the short-term gains of doing X worth the long-term cost? What will this do to my family? To my community?

One computer scientist, Robert Axelrod, wondered if there was a way to use a computer to model questions about what evolutionary strategies work best in the long run when considering whether to cooperate with an opponent or to, colloquially, screw them over. In 1984 he hosted an international competition where different strategies of cooperate-or-defect went head-to-head.

Some programs cooperated a certain number of rounds, then defected a certain number. Some cooperated or defected at random. Some almost always defected. A player got two points for defecting when the other cooperated; each got one point when both cooperated; neither got a point if both defected.

After millions of such iterations Axelrod added up the scores and in the next round pitted the most successful programs against each other.

The result of all these millions of games was stunning to Axelrod, and to game theorists in general. The most successful strategy in the very long term (in evolutionary terms) was so simple it was baffling: It was called Tit for Tat, and meant that a player would cooperate on the first round, then mirror whatever the opponent did in response. As long as the other side "played nice" the tit-for-tat player would do the same, and both sides made out better in the long run.

Did the player who initially cooperated sometimes get beaten by an opponent who was "selfish" (i.e., refused to cooperate)? Yes, of course, in the same way that anyone offering an act of kindness can be taken advantage of. So, a corollary also emerged: It may only be in one's best interests to screw the other side if you'll never see them again. If you're a business person, it may make sense to maximize your profit on any single transaction, but you can't afford to do that if you want an ongoing business relationship with the customer. Lower profit short term leads to higher profit long-term.

The evolutionary rule that emerged from all this was deceptively simple: If we're in any sort of community and you're nice to me, and I'm nice to you, we'll both be better off in the long run.

Once you start to think even a little about it, you start to notice game theory everywhere. Why does a stranger leap into a freezing stream to save a stranger? Why does a person with little money gives a large proportion of it to charity?

Or, take farmers who graze their cattle on public land—one farmer can maximize his profits by putting as many cattle as he can on the land, ruining it for others. From his standpoint this is rational, as he maximizes his own benefit. (This "tragedy of the commons" was well-known in English law). But he also destroys the land and prevents his neighbors from using the public resource, and disrupts the community he's a part of.

After those millions of computer interactions, Dr. Axelrod came up with a short list of traits shared by the most successful cooperation strategies. The most successful strategy is "nice," meaning it "will not defect before its opponent does…A purely selfish strategy will not 'cheat' on its opponent for purely self-interested reasons first."

Second, a successful strategy "must not be a blind optimist; it must sometimes retaliate."

Third, it must be "forgiving": "Though players will retaliate, they will cooperate again if the opponent does not continue to defect. This can stop long runs of revenge and counter-revenge, maximizing points [to both sides]."

Finally, a successful strategy must be "non-envious," meaning its main goal isn't to score more than the opponent. If that's the strategy's only goal, the community it "lives" in will spiral down.

Artificial Intelligence is all the buzz these days, so it's ironic that a simple computer contest forty years ago came up with some simple rules for being a good human being.

Image courtesy medium.com For more on the prisoner's dilemma, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prisoner%27s_dilemma#The_iterated_prisoner's_dilemm

Comments