Ventrilocution

- dtmillerlexky

- Jul 12, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 14, 2023

I'd been looking for a job my whole last year of college and had gotten interviews--the local PBS station, newspapers, several regional magazines, the city communications department—but no offers. I wasn't surprised; I had basically muddled through that last year and had no answer when they asked me where I saw myself in five years.

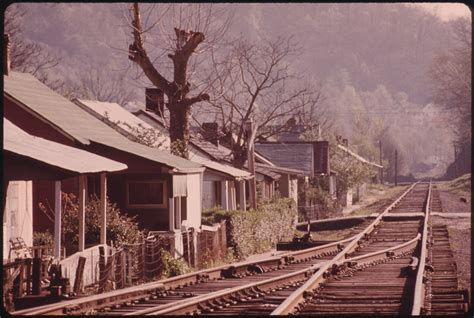

On a bulletin board in the English department I happened to see a help-wanted ad for the local radio station, WCLG. My first apartment in Morgantown (a run-down place just above a dance school, but that's another story) had been just across the street from the station, but I already knew the name from when I was a kid and my much older brother brought home a stack of brightly colored strips of paper with the station's logo at the top, listing the week's top forty songs.

Since then, the station had added an FM signal, with 3000 watts of power, and it broadcast the university's football and basketball games.

I had always loved music and had worked in the radio station at my previous college, which came in handy when I interviewed for the job with the WCLG general manager. They needed a copywriter, someone to write commercials and do public service interviews and very occasionally cover the air in emergencies; "dead air" meant listeners tuned out, which meant lower ad revenues.

I was given a writing and producing test, creating a twenty-second commercial for an imaginary business and cutting a tape for it. I easily passed the FCC test for a radio operator license and got the job, starting work a month before graduating. The money wasn't great but at least it was a job, and I could walk to work. And, however unglamorous the subject matter, I was writing words other people would hear. It seemed like a trick, some kind of ventriloquism.

I quickly learned to write punchy ad copy and how to tell a little story with just sound, including the things not to do—since many people would be listening in their cars, you couldn't use the sound of a siren or breaking glass, for example. (Oddly, you could use sound of engines revving and tires squealing, but not screeching brakes.) You could use talking animals and funny voices and the snik of a cigarette lighter or the thipthipthip of rain on a tin roof; you couldn't mention alcohol but could refer to "your favorite legal beverage."

I wrote five or six commercials a day, sometimes meeting with the client to talk about what they wanted to highlight. I learned early on to read my pieces quietly to myself, as sometimes what seems well-written doesn't work well out loud. I chose the music "bed" for each spot of thirty or sixty seconds, whatever the ad demanded, from a huge LP library of prerecorded music styles on vinyl records (these royalty-free tracks being called "needle drops").

I would oversee the commercials' production by DJs with pseudonyms like "The Real Doctor John" and "Bobcat" Jones. Every DJ was supposed to take their turn recording commercials, which some of them hated to do. I was amazed at their ability to nail a piece of copy in one or two takes, and there was something about hearing good voices say out loud words that I'd just written.

At the time, one of the funniest and best-written shows on television, WKRP in Cincinnati, was in its second season and it portrayed fairly accurately the daily rhythms of a radio station. There's something about radio that attracts oddballs, and the WCLG disc jockeys were all characters.

Bobcat was the quickest wit I'd ever encountered, and the program director Dr. John (I never knew his given name, as everyone just called him "Doctor") was a Robert Plant lookalike and thrilled the ladies at in-person events. I was always curious about what listeners thought disc jockeys looked like; unlike the Doctor, many of those with the most seductive voices were more like out-of-shape accountants in real life.

One of the drive-time guys was in a happy long-term three-person relationship, him and another guy and a woman, and all three would come to social events. They were all nice people and although (being from deep in a West Virginia holler) it wasn't something I'd ever heard of, it helped me realize that people construct their lives in whatever way works for them.

In addition to commercials I did weekly public service interviews, going out to talk to sports people or doctors or someone in the news, editing the interviews down to the thirty-minutes per week the station was (at the time) legally required to do.

I edited my own tape, cutting and splicing by hand using razor blades, since this was long before anything was digitized. At my old college station I'd learned to cut tape at a sharp angle to make one sound overlap slightly and transition seamlessly to the next, slicing a millimeter or two at a time to get it right. I'm not sure why I took such care--the station aired the interviews very early on Sunday mornings, when listenership must have topped out in the dozens.

Occasionally someone would call in sick and I'd have to cover part of their show just to avoid dead air until a real DJ could be brought in, but I was warned to play a lot of music and keep the talk to a minimum (since I wasn't a "personality"), which I did. On the few occasions I had to speak I was "Dave Marshall."

One of the AM DJs loved spinning out patter in the lead-in bars before the vocals in some hit from the 50s or 60s, and he was very good at timing it precisely. He was also having an affair, and although he wasn't supposed to leave the studio during his shift he would go outside to talk to his girlfriend, and I was by myself. Since I wasn't supposed to talk I just played record after record until he returned. These were still the small 45 rpm ones, and songs from that era were no more than three minutes long, so I had to get a new record cued on the second turntable before the first one finished, bringing the volume up on the second as the first faded out.

I pulled commercials and public service announcements from a "cart" board, basically a rack of eight-track tapes of twenty, thirty or sixty seconds each, and every fifteen minutes or so played a "house ad," one of those jingles with a mixed vocal chorus singing the call letters of the station and its hook line ("home of the hottest hits!" or whatever).

At that time the business model of record companies was to send out copies of their records to every radio station it could afford to, on the off chance that a song would get played and become a hit. Just as at my old college station, WCLG received hundreds more LPs every month than it could possibly play, and few that reached the station fit its top-40 rock and oldies format. The other records were to be thrown out unopened.

Everyone at the station hated disco, so those went directly to the dumpster. The rest were stacked by the back door, headed for the trash, and no one minded my having my pick of them. I took them home by the dozens and gave them at least one spin each, skipping a track by lifting the needle if a particular song didn't grab me. I found some great new favorites this way, like the Roche sisters, The Clash, and Elvis Costello. Some of the artists that I liked a lot would never have a top-40 hit but would have long careers, and it was interesting to watch them develop over the next several decades.

Since I was old enough to drive I'd haunted flea markets and secondhand stores for old record albums, the stranger the better, rarely paying more than fifty cents for one. Comedy, spoken word, instructional records, primitive rock and roll, I didn't care, and the stranger the better. (My hobby eventually paid for itself, once online auction sites came into being—someone, somewhere wanted those weird records.) The WCLG DJs appreciated my love of audio, though none shared my taste for the odder records.

One of the DJs, Larry, happened to be the son of one of the most famous ventriloquists of the 1950s, Jimmy Nelson. I have no memory of how I made the connection but Larry was stunned when I brought in a copy of the ventriloquism instructional LP his father had made in the 1950s—even he didn't have a copy. I was a little sad that he didn't.

I stayed with WCLG for a year, saving money before lighting out for the territories. I still wasn't sure what I wanted to do. As the WKRP theme song says, DJs are known for going "town to town, up and down the dial," and none of the DJs I worked with seemed particularly happy with where they were. I was no different. I enjoyed my time at the station but didn't see much future for myself in radio.

Comments