Free Ride

- dtmillerlexky

- Jul 26, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Sep 13, 2023

It wasn't long after Thomas Edison perfected the electric light that the more imaginative predicted a world with no dark corners—streets made safe, the night conquered, glittering marquees shilling movie stars ten times larger than life.

Horse-drawn carriages were replaced by electric cable cars and, when radio became the first popular mass entertainment medium, broadcast towers sprang up in cities across America. Soon the hum of electric wires became the background noise of everyday life.

Electricity changed everything, and from the start there was a critical need to train young men—they were almost all men at the time—to understand and build and repair all those machines.

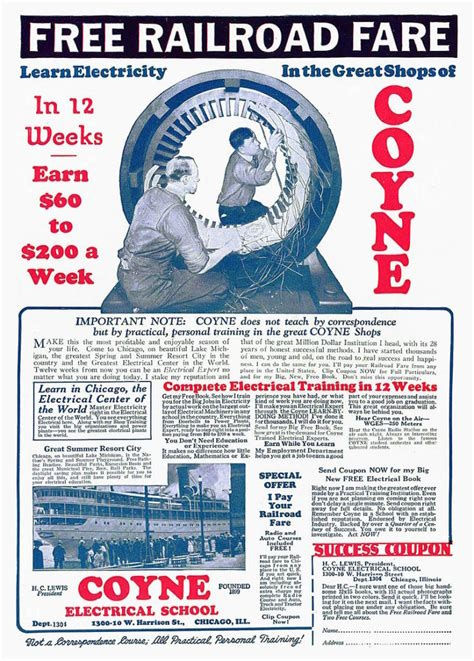

B.W. Cooke, a Chicago engineer, saw this demand coming. In 1899 he founded Coyne Electrical School, and it would thrive for more than a hundred years, half of that with him at the helm.

Coyne grew with the American Century, fresh interest in its training growing during wartime and the Space Age of the 1950s and 60s. Just after the war, ten thousand telephones a day were being installed in the US, and factories that had turned out bombs were retooled to make washing machines and vacuum cleaners and cabinet radios and televisions. All these industries demanded well-trained and up-to-date electricians, and soon the average American home had countless appliances and entertainment devices that depended on repairmen to keep them running.

Coyne became so successful that for more than fifty years it could afford to advertise widely, with a unique hook: the school would pay a student's transportation to and from Chicago by rail for anyone enrolling. The ads appeared in newspapers, movie magazines, on billboards. Thousands signed on and became skilled in anything having to do with electricity.

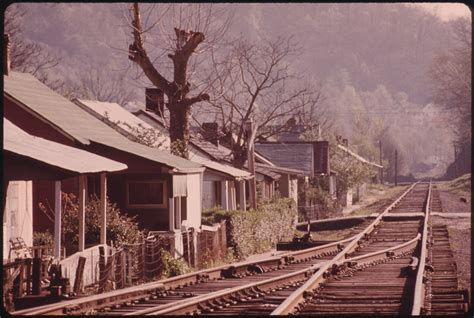

In 1956, a year before I was born, my father saw one of Coyne's ads on the back of a comic book my brother brought home. My father aspired to a college education but it was never to be; he was working as a general laborer in the coal mines, the only job available in West Virginia, and caring for his own growing family, an ill wife, and his elderly parents, all while dealing with PTSD from his time in the war.

My father quit his job and took advantage of Coyne's offer of free railroad fare, moving to Chicago for a condensed course in electricity. When he came back he passed the exam to become a mine electrician and got a new job at higher pay and with safer working conditions. It was never easy but it was easier than shoveling coal, and he was able to lift our family into the lower rungs of the middle class.

My father loved his short time in Chicago. It was the first big city he'd spent any time in, as was true for many other young men who enrolled in Coyne. They all took their experiences back to the small towns they'd come from and kept all those machines running. In a way they were the unsung heroes of America's prosperous, can-domid-century.

In the 1960s Coyne Electrical merged with the American Institute of Engineering and Technology to become Coyne American Institute and expanded its courses to provide much of what any small college would, and their focus shifted to accommodate the then-new microprocessor revolution.

But time caught up with the school in 2022, and it closed its doors, partly because of the pandemic, but also because many consumer items are designed to be thrown away once they break down, and more complex machines now require a depth of specialization that no small school can offer.

But a run of 120 years isn't bad.

Comments