The Great Goettge - Part 2

- dtmillerlexky

- Sep 6, 2023

- 9 min read

This is the second of two parts about football star Frank Goettge ("GET-chee"). You may want to read last Wednesday's post for context.

August, 1942. America was trying for a comeback. The Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor wiped out much of US air power and opened the South Pacific to the Japanese as a stepping stone toward Australia and New Zealand.

Without footholds in the region for supplies and refueling, American influence in the entire hemisphere would be boxed in. In football terms, the US’s passing game had been shut down, and its ground game wasn’t much better.

Despite some victories, such as the Battle of Midway, America was clearly in a race against time and began gearing up companies from its prestigious 1st Marine Division to begin the struggle for control of the long archipelago that seemed to lead directly to Japan’s doorstep. [i]

A massive shipbuilding, armament, and amphibious assault training effort was underway, and the Marine Corps was expecting to be deployed to the South Pacific very late in 1942 or early 1943.

Instead, ready or not, the Division was pulled from their training in New Zealand to land on the tiny island of Guadalcanal on August 7 of '42.

Intelligence had detected that Japan was building an airstrip on the small island and aerial photographs showed it close to being completed much more quickly than America's military leaders had anticipated. The First Marine Division was ordered to retrain and resupply at breakneck speed. The Marines gave the chaotic planning their own code name: Operation Shoestring.

Frank Goettge, by now a Lieutenant Colonel,[ii] was in Philadelphia that July when he got his new orders: He was to become the Chief Intelligence Officer for the 1st Marine Division, assigned to Headquarters Company. The assignment made sense—Goettge had intelligence experience from his time in Haiti. The new job came with a promotion to full colonel.

Just as the Marines had their training and preparation reduced from months to weeks, so too had intelligence officers been given little time to gather information. No one knew the first thing about the island. Reconnaissance flights were risky and almost no Westerner spoke the native ghari language.

The Division's landing on Guadalcanal was eerily quiet; they knew the island was held by the Japanese, but there were no mortars or machine guns to repel them. The Marines crept ashore and began to set up camp and gingerly probe the edges of the Japanese force.

The first few days it must have seemed to the Marines that the Japanese didn’t want to fight. In fact, the Japanese had outrun their support and were desperately low on food and morale, as their captured diaries would later attest.

But they still had mortars and their long-gun ships just offshore and the Bushido warrior code on their side. Bushido required that they die rather than surrender.

The Marines would soon come to understand the same hunger the Japanese felt. Two days after the Marines landed, and before more than a fraction of their supplies and ammunition could be offloaded to the island, Japanese battleships and mortars attacked the Navy ships, driving them away from the island. America couldn’t stand to lose any more ships.

The Marines watched the boats pull away. It would be four months before new supplies could be brought in and the first wave of Marines relieved. By then many had lost forty or fifty pounds and were wasting away from malaria and the many other diseases endemic to the tropics.

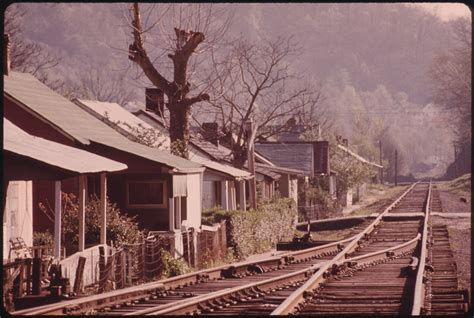

Goettge arrived on the island a few days after the First Division that August. He and his photographic officer, Lieutenant Karl Thayer Soule, drove a jeep around as much of the island as they safely could, looking at the natives' rough shacks and the few artifacts the Japanese had left behind when they abandoned the area for higher ground as the Marines came ashore. [iii]

The 6'2" Goettge hadn’t lost his commanding presence. Soule describes meeting him for the first time: “Colonel Frank Bryan Goettge was as big as an ox. Rising from behind his desk, he looked like a mountain, a huge mass of a man towering above me. He had gray hair, glasses, a garden of ribbons on his shirt, and an almost fatherly look in his eyes. ‘Welcome aboard, Lieutenant.’ The voice fitted the man, firm and heavy, but friendly and warm. We shook hands with a tight, firm grip.”[iv] They began making maps from the few aerial photos the Corps had been able to obtain.

Goettge’s team began to analyze what little was known about the Japanese on the island, frustrated that they didn’t have better intelligence on the size and location of the Japanese force. The short-handed and badly-supplied Marines weren't ready for a full-on assault on the near-complete airfield. But despite the Navy’s departure, a lack of food and other supplies, and a force of uncertain size between them and that airfield, the Marines had to take the initiative somehow.

If the Japanese held the island long enough to make the airfield operational, their air power could cut off American supply lines and give them control of the Solomon Island chain. The entire American effort in the South Pacific could be for naught. Japanese aircraft taking off from the field could rain bullets directly down on the Americans, by land and by sea.

On August 12, 1942, Goettge received word that a patrol had come upon two stray Japanese soldiers. The first they killed. The second raised his hands in surrender and they captured him.

He was a warrant officer by the name of Tsuneto Sakado.[v] After the Americans had given him food and a liberal supply of alcohol, he told them, via one of the few Japanese-speaking Marines on the island, that just west of a sandspit at the mouth of the Matanikau River was a big group of Japanese who were starving and would surrender. Goettge recalled that in fact, a few days earlier a patrol had spotted a large white flag at that position.

Goettge believed Sakado and thought the captured Japanese could be an intelligence goldmine. He and a First Sergeant organized a 25-member patrol to capture the starving Japanese.

The patrol included most of Headquarters' intelligence officers, the only surgeon on the island, a handful of riflemen, and the Marines' only Japanese interpreter. The intelligence officers went because more infantrymen couldn’t be spared from the Marines’ fragile beachhead.[vi]

The Division Commander, Lieutenant General Alexander Vandegrift, wasn’t at all sure Goettge's plan was a good idea. Goettge had to persuade him that the captured Sakado was telling the truth and that the Japanese could be taken by a small squad of Marines.

Vandegrift relented but warned Goettge not to land near the Matanikau River (see map below) because scouts had spotted a large Japanese contingent there. Goettge was ordered to land well west of Point Cruz and the river.

The patrol got a late start, setting out in a small "Higgins" boat the next evening. Sakado led the way with a rope around his neck. Goettge's plan was to land beyond the river, shelter for the night, and close on the enemy in the morning.

Because of the late start, unfamiliar tides, and difficulty seeing the coast in the dark, they didn't land at the site originally planned. Instead, just as they'd been warned not to do, they went ashore too early, just 200 yards from the mouth of the Matanikau, rather than west of Point Cruz.

The prisoner Sakado told them not to land there, saying No! in Japanese: Iie! [vii] By allowing himself to be captured he'd broken the Bushido code and knew he would be killed by his own soldiers.

Goettge's small boat ran aground on a sandbar and the Japanese heard the coxswain gunning the engine back and forth in a vain attempt to free it. The Marines piled out and ran for a stand of banyan trees just beyond the beach, directly toward the Japanese.

The Japanese saw what must have seemed a gift from God: an American colonel still wearing his insignia, leading a traitor on a leash.

This would be the first contact between Japanese and American forces on the island.

Goettge was shot in the head and died instantly, as were Sakado and a sergeant. The rest of the patrol stayed close to the boat all day and returned fire through the night, falling one by one to the spray of hidden machine guns.

That night the stranded Marines threw up tracer bullets and the Marines back at the base saw them but had no idea of the carnage taking place four miles away.

Two men escaped the beached Higgins boat in the night, swimming back to the base through shark-infested waters and concertinas of sharp coral.

Three of the last remaining men trapped at the sandspit were killed just as the sun came up the next morning. One of the remaining few at the boat hit the water and began swimming back to the base. That sergeant, "Monk" Arndt, described looking back at Japanese swords “flashing in the sun” as they dismembered the dead and wounded Marines.

Patrols the next day searched the area where Goettge was supposed to have landed, finding nothing. Over the next few days other patrols looked closer to the Matanikau and found torsos and feet with boots still on them.

A tropical storm soon washed the mouth of the river clean of all evidence of the Goettge patrol.

Word spread rapidly that the Japanese weren’t waging the kind of war most Marines had been trained in; therefore, neither would the Marines feel bound by the Articles of War on how to treat prisoners.

No white flag of surrender as had been described to Geottge was ever found. It may have been a regular Japanese flag, which is all white except for the rising sun in its center. On a windless day it could easily be mistaken for a flag of surrender.

The Marines charged with taking Guadalcanal had been in a hole, and Goettge's misadventure dug them in further. The loss of many of their intelligence officers, their surgeon, and their interpreter made a dire situation worse. The decision to leave at night, to land in the wrong place, and to face an enemy of unknown size or position was the kind of error few would have expected from the golden boy, Goettge the Great, the Unstoppable.

As word of the doomed patrol spread, the Marines were stunned that they had lost the first skirmish in the battle for control of the island.

The Marine Corps hushed up the Goettge mistake for years, since it would have been terrible for morale, but word of Japanese atrocities quickly got around the island. Marines resolved that they would be equally bloodthirsty and inhumane. The Guadalcanal fight became fueled by a “brutish, primitive hatred, as characteristic of the horror of war in the Pacific as the palm trees and the islands.”[viii]

Goettge’s decision to undertake the patrol is still debated today. Was his intelligence simply outdated? Was he wrong to believe Sakado’s story? Was Sakado lying? Was it Vandegrift’s fault for acceding to Goettge’s argument? We'll never know.

In the end, the near-starving Marines took the unfinished airfield and held it against fierce Japanese assaults. There is no way to gauge how much more difficult the loss of the divisional intelligence officers made their job.

The Goettge Patrol accomplished two things. First, it demonstrated to the Marines, and to America, that they were fighting a new kind of war. The enemy was no longer another human being but a sub-human, evil personified.

Japanese bones became trinkets for Marines to send back home as souvenirs. Life magazine in May 1944 featured a smiling young woman contemplating the lovely skull her boyfriend sent to her from the South Pacific.[ix]

The second thing the patrol accomplished was to forever link the name of a small-town boy, once the country's best football player, to a single pivotal and potentially disastrous wartime decision.

The Army, Navy, and US Air Force all still field football teams. The Marine Corps dropped its football program after the 1972 season.

Frank Goettge isn't forgotten--the Field House at the Marine Corps' Camp Lejeune is named for him.

[i] For an after-action summary of the events on Guadalcanal, see https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/USMC-C-Guadalcanal.html [ii] For a summary of Goettge’s assignments, see https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=86192455 [iii] Thayer’s story is briefly covered in https://marines.togetherweserved.com/usmc/servlet/tws.webapp.WebApp?cmd=ShadowBoxProfile&type=Person&ID=102305 [iv] Soule went on to become one of the war’s best photographers and a collection of his work appears in the Thayer Soule Collection (COLL/2266) at the Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division. The University Press of Kentucky published a collection of his work, Shooting the Pacific War: Marine Corps Combat Photography in WWII in 2000. [v] https://marines.togetherweserved.com/usmc/servlet/tws.webapp.WebApp?cmd=ShadowBoxProfile&type=Person&ID=102305 [vi] The patrol has been written about widely. A slightly fictionalized account was featured in Richard Tregaskis’ bestseller Guadalcanal Diary. [vii] This is quoted in https://marines.togetherweserved.com/usmc/servlet/tws.webapp.WebApp?cmd=ShadowBoxProfile&type=Person&ID=102305 [viii] Eugene Sledge, With the Old Breed, [ix] Life Magazine, May 22, 1944. “When he said goodbye two years ago to Natalie Nickerson, 20, a war worker of Phoenix, Ariz., a big, handsome Navy lieutenant promised her a Jap. Last week Natalie received a human skull, autographed by her lieutenant and 13 friends, and inscribed: ‘This is a good Jap—a dead one picked up on the New Guinea beach.’ Natalie, surprised at the gift, named it Tojo.”

Photos courtesy US Marine Corps Museum and Life Magazine. Map courtesy RememberedSky.com

Except for credited photos and quotations, all material on this blog copyright David Thurman Miller 2023.

Comments