The Great Goettge - Part 1

- dtmillerlexky

- Aug 30, 2023

- 9 min read

Updated: Sep 5, 2023

Football season two-part special:

How the best fullback of his day nearly lost the war

The Wednesday essays this week and next are excerpts from a much longer unsold magazine piece. Football has overtaken baseball as our national sport, which I think says something about America. As George Carlin put it: "Football represents something we are--we are Europe, Jr. What was the Europe game? 'Let's take their land away from them!... Of course, we only do it ten yards at a time. That’s the way we did it with the Indians, little by little. First down in Ohio–Midwest to go!" It's not surprising that American football has always been identified with the military. And, Frank Goettge (pronounced GET-chee) is one of the main reasons.

The Devil Dogs were coming. The Marines were going to invade Ann Arbor.

At Quantico, Virginia, two thousand young Marines prepared to board five trains in forty-two Pullman coaches bound for Ann Arbor on a cold November 8, 1923.[i] The men were there by choice: many had spent a month’s paycheck to travel to the game.[ii]

The Corps’ football team was only in its third year but had been undefeated each of the first two, and again dominated in 1923, with only a season-opening loss to Virginia Military Institute to mar their record. Other than VMI, no opponent had scored a point, against 117 for the Marines. Coach John “Jack” Beckett had built a powerhouse team and he knew it.

Service teams had dominated football since America entered the First World War and drafted all able-bodied men. Many took up football there and service teams racked up win after win against college teams in the few years following the war. Inter-service rivalries took precedence over games against civilians.

The great Marine Corps teams of the early 1920s drew on the best players in the entire Corps, some of them recruited just to play football. Brigadier General Smedley Butler—"Old Gimlet Eye"—“ordered the Marine Corps to field winning football teams and build a stadium good enough for those teams... Football is like war. Who in hell wants to lose a war?”[iii]

Butler reportedly “scoured the Corps from 1921 to 1924 in his effort to secure team players. Every battleship detachment, Navy yard barracks and Marine post was urged to send its best.”[v] It was a canny move. Every away game became a fresh recruiting tool for the Corps, and Butler attended every game.[iv]

Frank Goettge was clearly the star of the Corps teams. At 6'2" and 220 pounds, he was a dominant fullback, tough as nails and hard to bring down. He quickly became known as "The Great Goettge," the best football player on any of the service teams and arguably the best player in the country.

Goettge’s reputation preceded him. Before one inter-service game a newspaper columnist described the atmosphere: “Streetwide banners generously distributed throughout the city blatantly exclaimed how Army would stop Goettge. Stop Goettge! It was a mighty cry and a courageous attempt. But Goettge was not to be denied, and neither were the team nor the faithful on the sidelines and in the stands."[vi]

Goettge and his 1922 team dispatched the Army’s Third Corps 13 to 12 in that game, with the Secretary of War, the Secretary of the Navy, society leaders, and military brass all in attendance, along with "the father of American football," Walter Camp, and the sixty thousand civilians who crowded Baltimore Stadium.

Goettge would play four nearly-unbeaten years for the Marine Corps. He earned his nickname “the Great” with masterful play against the best of the other service branches and eastern college teams. He was “even better than Jim Thorpe” in the words of a New York Times columnist, and Walter Camp declared him the “all-time greatest football player.” Goettge was unstoppable.

The 1922 team is considered the Corps’ finest, and the last season when the Marines could still be considered underdogs. The perfection it neared would get further out of reach the next two seasons.

The pendulum that had made the service teams so powerful a few years earlier, during and just after the war, was beginning to swing back to college teams, as a fresh crop of young men became available. Notre Dame’s legendary Four Horsemen backfield was formed the same year that Harold “Red” Grange at Illinois started his long coaching career.

The balance of football began to shift away from service teams and the Ivy League toward middle America and then California, establishing it as a truly national sport.

But today, November 8, 1923, the Corps team looked unstoppable. It would see what it could do against the best college team, the Michigan Wolverines, in the first non-collegiate game the Wolverines had played in a quarter-century. It wouldn't be easy for the Corps--Michigan was unbeaten and untied.

From the start, it was a very personal game for both sides. Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby was a Michigan grad and had played center for the team in 1895. He and Michigan athletic director Fielding Yost arranged the match with the Marines and it immediately became an informal championship between the military and civilians.

Denby sat with Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. and not far away were Michigan’s governor and one of its senators, along with Henry Ford and Marine Corps Commandant John A. Lejeune. Forty thousand fans packed Ferry Field, including the Marine Corps marching band.

A little after two p.m. two thousand Marines marched in in in tight formation and formed a capital-letter M on the center of the field to honor their hosts. The Marines’ very large bulldog mascot—the Detroit Free Press said "his mother must have been a hippopotamus”[vii] —marched in alongside them. The Marines broke ranks and filed to their seats.

The apparently ever-cheerful Goettge—nicknamed "the Smiling Lieutenant”[viii]—pulled on his leather helmet. (The face-guard hadn't been invented, and helmets were not even required in college football until 1939[ix].) He immediately made his presence known, helping drive the ball 89 yards from the opening kickoff and scoring a touchdown on a short run. It was the first time the Wolverines had been scored on all season.

Goettge was everywhere, playing both offense and defense and punting and returning kicks. It looked as though he would be as commanding against Michigan as he had been in the Corps’ previous games.

Most of the Marines’ offense was built around running him from a few simple formations, for good reason. At almost two hundred pounds, tall and broad, Goettge “when in motion travels fast and hard enough so that it looks from the sidelines as though no single human being—perhaps no pair of them—could ever stop him….His method was to pick out a distant spot and charge for it with a fine disregard for all that stood in his path.”[x]

But if Michigan could stop Goettge, it could stop the Corps, it was as simple as that.

The Marines’ dependence on Goettge was their Achilles’ heel, as the first half became a war of attrition. Goettge gave it his all: “He did all the passing and kicking and carried the ball more than all of the other backs combined. Once Michigan figured out how stop him they stymied the Quantico team.”[xi] Michigan kept Goettge out of the end zone after that first score.

Michigan's offense depended more on slashing off-tackle runs than direct attacks at the Marines’ strong center line. (Passing wasn't yet much of a factor in football—since its introduction in 1906 it had been discouraged by rules such as giving any ball that went out of bounds to the defense at that yard line.) The Maize and Blue simply ran the ball outside again and again.

The first quarter seemed to go on long past fifteen minutes, and in fact it did—a bizarre error by the timekeeper extended it to an official 33 minutes, for a total first half of 52 minutes.

With a great kicking game the Wolverines pressed the Corps team back to its own end again and again and Michigan scored just before halftime to lead 7-6.

The Marine Corps is actually a part of the Navy, and the Corps considered Secretary Denby one of their own. At halftime the Marine Corps band marched across the field to his box seat in front of the Quantico cheering stand at the north end of the stadium. A sergeant addressed Denby directly: “Edwin Denby, the Marines want you to come home.”[xii]

Lejeune and Butler also moved to the Marines’ side of the gridiron at halftime.

Goettge had no better luck in the second half, and Michigan found some unlikely heroes. In the fourth quarter, on his first play as a Big Ten football player, Michigan substitute quarterback Tod Rockwell scored a touchdown on a fake field goal. To add insult, Goettge’s pass was intercepted late in the game and run back for a touchdown, setting the final score at 26-6.

With the lengthened first quarter, the game had lasted 78 minutes; the Marines probably thought it would never end.

General Butler’s reaction to the stunning loss isn’t recorded but Secretary Denby pronounced it “A great day, boys, and a great game, even if I did want to see the Marines win!”[xiii]

Not only did Michigan beat the Marines, it finished that year with a perfect record, 8-0, winning the Big Ten and national championships while outscoring other teams 150-12.

The Corps, meanwhile, would win the rest of the season’s games except for a tie, and finish 7-2-1. (The tie would come the following week against the “powerhouse of the west,” Lawrence, Kansas’ redundantly named "Native American Haskell Indian Nations Fighting Indians.")

The almighty Corps was no longer so almighty. The Great Goettge was still great, but at 28 maybe losing a step, and the game was changing around him.

His “coming out” for Marine Corps football had been in 1921, when he was called back from Haiti, but he had been playing since 1911 at Barberton High School, then semi-pro in Barberton in 1915, and then for a year at Ohio University. He did all this with little protective padding and ther than a thin

leather helmet.

But Goettge wasn't done. He would play one last season for the Marines, in the fall of 1924. The Corps command ruled that four years of playing eligibility was enough. His final team racked up seven wins and another tie.

The New York Giants reportedly offered Goettge a pro football contract for $10,000, which would have made him the highest-paid player in the fledgling NFL. Goettge chose to remain in the Corps.

The Quantico Marines would continue to field strong teams for a few years, until the Depression and the rise of the San Diego-based Marine Corps as the top service team. Control of the Quantico team passed from Smedley Butler to a nameless major in Washington, DC, and Jack Beckett coached his last Quantico team in 1924 before heading west to San Diego.

By 1929 the Corps was facing off against not the best college teams but a gallimaufry of opponents such as the Seaman Gunners, the Baltimore Firemen, and the Navy Pharmacists. The Corps still beat them, but it wasn’t the same. And they'd lost their star player.

Goettge would stay on as an assistant coach for the Corps team one more year before shipping out to the American Legation in Peking, where he served as detachment athletic officer, among other roles.

Soon he would be back stateside as an aide to the Commandant of the Marine Corps and then man aide in Herbert Hoover's White House. He did a tour in China before becoming Commanding Officer of the Marine detachment at Annapolis, Maryland.

He was destined for great things, everyone agreed. Probably a career in politics. He would still be a young man when his time in the Corps was up in a few years. The handsome, quiet Goettge had a lot of admirers in Washington and everyone remembered his football career. In June, 1941, Goettge was assigned to the 1st Marine Division as chief intelligence officer. War was on the horizon. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor it became clear that the entire South Pacific would become a theater of war, as Japan sought to establish bases and airfields throughout the southern hemisphere.

When Washington decided that the First Marine Division would be sent to interrupt the Japanese construction of an airfield on the tiny but strategically essential island of Guadalcanal, Goettge was sent ahead to prepare maps and plan the Marines' counter-offensive.

But on Guadalcanal Goettge made a big mistake—one that could have meant disaster for the US and threatened the entire Pacific Theater counter-offensive.

That's next week.

[i] The Michigan Alumnus, Vol. 30, November 15, 1923, p. 171. [ii] http://www.quantico.usmc.mil/Sentry/StoryView.aspx?SID=776 [iii] Gunn “The Old Core” [iv] Ashman [v] Gunn [vi] https://archive.org/stream/marinebarracksqu00unit/marinebarracksqu00unit_djvu.txt [vii] Detroit Free Press, Sports/Financial Section, November 11, 1923, at 1. [viii] The nickname is quoted in The Leatherneck, Vol. 15, 1932. [ix] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_football_helmet [x] Michigan Alumnus at 171. [xi] DFP 11/11/23 at 1. [xii] Detroit Free Press, November 11, 1923, at 22, 25. [xiii] Michigan Alumnus November 15, 1923.

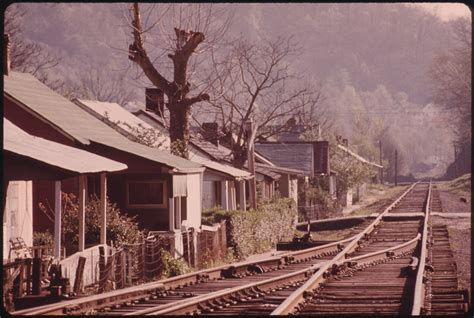

Photos courtesy Library of Congress.

Except for credited photos and quotations, all material on this blog copyright 2023 David Thurman Miller.

Comments